Over 200 galleries and exhibits will explore subjects and events of national interest and global significance. Visitors will explore the accomplishments and missions of the Coast Guard and its remarkable history woven into five themed storylines: The Safety Deck feautures the Lifesavers Around the Globe wing, along with Coast Guard vessels. The Security Deck features the Defenders of Our Nation and Enforcers on the Seas wings. The Stewardship Deck tells the story lines of Champions of Commerce and Protectors of the Environment. The examples below the represent kind of stories to be included in the exhibits.

Stories that Matter: Vice Admiral Manson K. Brown

The Honorable Manson K. Brown, Vice Admiral, USCG (Ret.), a Washington, DC native, is the son of public servants. At the age of 17, he entered military service as a cadet at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy with the Class of 1978. His journey with the Coast Guard spanned 40 years. In 2010, he became the first African-American to achieve the rank of Vice Admiral in his service.

Early assignments ranged from duty as an engineering officer aboard the icebreaker GLACIER to working as the Military Assistant to the U.S. Secretary of Transportation. In 2004, he volunteered to fill a key leadership gap in Iraq as the Senior Advisor for Transportation for the Coalition Provisional Authority. Working in a combat zone, he oversaw restoration of Iraq’s transportation systems, including major ports. He commanded operations at every level, culminating as Commander of Pacific Area where he oversaw all Coast Guard operational activities throughout the Pacific Rim.

After retiring from the Coast Guard in 2014, he was nominated by President Barack Obama as an Assistant Secretary of Commerce at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. As NOAA Deputy Administrator, he also championed an effort to enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion throughout the organization.

He holds Master of Science degrees in Civil Engineering from the University of Illinois at ChampaignUrbana, and in National Resources Strategy from the National Defense University. His top military decoration is the Coast Guard Distinguished Service Medal. In 1994, he became the first recipient of the Coast Guard Captain John G. Witherspoon Award for Inspirational Leadership. In 2012, the National Society for Black Engineers honored him with the Golden Torch Award and The Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard designated him as an Honorary Master Chief Petty Officer. In 2014, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People honored him with the Meritorious Service Award.

Stories that Matter: The earliest female lighthouse keepers

Elizabeth smith, 1830-1856, Old Field Point, NY

The female keepers at Old Field Point never reached national fame like Ida Lewis at Rhode Island’s Lime Rock Lighthouse, but when Keeper Edward Shoemaker died in December of 1826, his widow assumed his post for the following six months. She (ironically, her name is not noted) was the first female keeper in the Third District and one of the first in the nation.

The next keeper was Walter Smith, who took over in June 1827. When he passed away in April 1830 his wife Elizabeth Smith, who was already familiar with station duties from assisting her husband, took over as head keeper. She remained at her post for twenty-six years, after which she was succeeded by another woman, Mary A. Foster.

Ann Davis, 1830-1847, Point Lookout, MD

Ann Davis was the first female keeper at Point Lookout Lighthouse. In 1830, she took over the duties of her father James Davis, after he died during his first few months of duty. Much has been made about the notations on Ann's early contract that prohibited her from selling liquors on lighthouse property. Apparently, Miss Davis went on to be a well regarded keeper after the selling of liquor was resolved. In a report made in 1840, Miss Davis was complimented by a supply boat captain: "Miss Davis is a fine woman...and I am sorry she has to live on a small naked point of land".

Davis served for 17 years until she is presumed to have died in 1847.

Rebecca flaherty, 1830-1837, Sand Key, FL

The first keeper of Sand Key Lighthouse was slated to be Joseph Ximenez. However, Keeper John Flaherty and his wife Rebecca were having a terrible time adjusting to their isolated life in the Dry Tortugas, so the collector of customs at Key West, William Pinkney, arranged for the two keepers to trade assignments. Shortly after the Flahertys arrived on the island, Sand Key Light was exhibited for the first time on April 15, 1827. With fishermen, wreckers, and picnickers from Key West frequenting the island, the Flahertys thoroughly enjoyed their new social life. Their joy, however, was short-lived as John fell ill in May 1828 and passed away in 1830. Rebecca remained on the island and was appointed keeper after her husband’s death.

In June 1831, William Randolph Hackley, an attorney in Key West, recorded the following account of a visit he made to Sand Key Lighthouse: “The wind was so light that we did not get to the key until 12…I went up to the lighthouse. The light is revolving and is one of the best in the United States. It is kept by Mrs. Flaherty…She, with her sister and a hired man, are the only inhabitants of the key and sometimes there are none but the two females…The length of the key is from 150 to 200 yards and the average breadth 50 … [We] remained till evening and, having spent a pleasant day, returned to town at 8:00 P.M.”

Captain Richard Etheridge: Pea Island Lifesaving Station

Captain Richard Etheridge (left) led the first all-black crew in the U.S. armed services.

Captain Richard Etheridge was born a slave in the Outer Banks of North Carolina. A Union Army veteran, Etheridge became the first African-American to command a Life-Saving station when the service appointed him as the keeper of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station in North Carolina in 1880. The Revenue Cutter Service officer who recommended his appointment, First Lieutenant Charles F. Shoemaker, noted that Etheridge was "one of the best surfmen on this part of the coast of North Carolina." Soon after Etheridge's appointment, the station burned down. Determined to execute his duties with expert commitment, Etheridge supervised the construction of a new station on the original site.

He also developed rigorous lifesaving drills that enabled his all-African-American crew to tackle all lifesaving tasks. His station earned the reputation of "one of the tautest on the Carolina Coast," with its keeper well-known as one of the most courageous and ingenious lifesavers in the Service.

In the Lifesavers Wing, the Pea Island Lifesaving Station Immersive Gallery places the visitor in the late 19th century rescues off the coast of North Carolina.

A Fitting Memorial: Coast Guard Medal for SA William Flores

by MCPOCG Vince Patton, USCG (Ret.), Museum Association Board of Directors

On the evening of January 28, 1980, there was a collision between the Coast Guard Cutter BLACKTHORN and the 605-foot oil tanker, SS CAPRICORN near the entrance to Tampa Bay, FL. Immediately, the BLACKTHORN rolled to port and capsized before the ship’s personnel could prepare for an orderly abandon ship. Many shipmates displayed bravery amidst the frenzied effort to get everyone to safety. Sadly, 23 lives were lost that night.

The death toll may likely have been much higher if it weren’t for the courage of one crew member whose heroism went unrecognized for over two decades following the tragedy.

Early in my tenure as MCPOCG, I attended the memorial gathering for the USCGC BLACKTHORN on January 28, 2000, which commemorated the 20th Anniversary of the tragic accident.

After the memorial service, three crew members who survived the sinking approached me, and told me that one of the perished shipmates was never recognized for his heroism. All three believed that it was the efforts of this newly reported Coastguardsman that saved their lives. The problem was they weren’t sure of his name because he was new to the crew, and they barely knew him. What they did know was that he was one of the three recent arrivals that reported on board BLACKTHORN within the past four months prior to the accident.

They told me that they all remembered seeing this crewmember tossing life jackets out from the locker as the ship began going down. When he couldn’t get all of the flotation vests out quickly enough, he took off his belt and tied the locker door to the railing, so the life jackets would freely fall out.

One of the survivors reported that he saw this unidentified hero go into the ship as the BLACKTHORN capsized, to assist in opening a jammed hatch where several crew members were trying to get out.

The survivor shipmates told me that they had given statements during the board of inquiry about this unidentified crew member. All three agreed that they believed it to be SA William Flores. Flores had only been on board the BLACKTHORN for four months or so after completing boot camp.

Although his shipmates were assured that their statements about Flores would be reviewed and considered for recognition, the event I attended marked the 20th anniversary of the accident, and they had not heard any news as to whether the Seaman Apprentice was given any recognition for his action.

I knew I had to investigate this matter further. When I got back to Coast Guard Headquarters, I engaged my staff to look into this matter. We had to obtain the board of investigation records from the National Archives, about 800 pages of the full details surrounding the cause of the accident, as well as individual testimonies from all of the BLACKTHORN survivors. Our review took several weeks because of the volume of information provided. My team and I confirmed that, just as the BLACKTHORN survivors had reported, there were 11 statements regarding the unidentified crewmember credited with saving so many lives.

Due to darkness and the general commotion on the deck, many of the survivors were unable to definitively determine who had acted so courageously on behalf of others. However, four of the eleven statements specifically named Flores with varying degrees of certainty that it was their new shipmate.

Once my staff and I gathered the details, I contacted the Coast Guard Investigative Service, which is standard procedure to begin an awards investigation to formally document the information and prepare evidence for the Coast Guard Medal. After seven months of reexamining the reports, the evidence factually documented that the unidentified crewmember was indeed Seaman Apprentice William Ray “Billy” Flores.

MCPOCG Vince Patton and RADM Paul Pluta salute SA Flores

I personally wrote the award recommendation and citation for the Coast Guard Medal, which was later approved by the Coast Guard Awards Board in July 2000.

MCPOCG Patton embraces Mr. and Mrs. Robert and Julia Flores

On Sept 16, 2000, along with the 8th District Commander, RADM Paul Pluta, I had the privilege to present the Coast Guard Medal posthumously to SA Flores’s parents, Robert and Julia Flores. The ceremony was held at his gravesite in Benbrook, TX.

The quest to research the actions of SA Flores became something of a spiritual journey for me. As I read through the board of investigation, and the follow-on interviews, I couldn’t help but visually put myself aboard, watching this whole action as it unfolded. I was consumed with the intention to ensure that Flores be properly recognized for his unwavering action. Most amazing was that he had only been in the Coast Guard for about eight months at the time this happened!

Immediately after RADM Pluta and I made the formal presentation of the Coast Guard Medal to Mr. and Mrs. Flores, we both knelt before their son’s headstone. I then spoke to SA Flores’s headstone and said, “Job well done, Shipmate. Rest in Peace and thank you for your selfless service.”

Stories that Matter: Barrier Breakers Oliver Henry and LTCDR Carlton Skinner

Oliver Henry came from a military family. His father and namesake, Oliver T. Henry, served in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War I and two of his younger brothers would serve in the Army in World War II. Eighty years ago, in 1940, after working several years as an auto mechanic, Henry enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard at the Baltimore recruiting office. After basic training, he shipped out to New York and served aboard the cutter Manhattan and then the Champlain.

Oliver Henry early in his Coast Guard career. (U.S. Coast Guard)

In 1941, he shipped out on Cutter Northland. Aboard Northland, Henry participated in numerous historic events and operations. In September, a few months before the U.S. entered World War II, Northland began operating in the Greenland theatre of operations. A few months later, the cutter took into custody the foreign sealer Buskoe, considered by some the first capture by U.S. forces of an enemy vessel. A month later, the Coast Guard established a unified Greenland Patrol with Northland acting as flagship under famed officer “Iceberg” Smith. In 1942, Northland rescued several aviators forced down on the Greenland icecap—the last aerial rescue resulted in the deaths of heroic Coast Guard aviators John Pritchard and Benjamin Bottoms. In 1943 and 1944, Northland played hide-and-seek with German trawlers and enemy weather stations hidden on Sabine Island and on Greenland’s eastern coast. For example, in July 1944, the cutter’s crew discovered the remains of the German trawler Coburg and, in September, chased the trawler Kehdingen for 70 miles through ice flows before its Nazi crew scuttled it and surrendered.

Lt. Commander Carlton Skinner

During his first cutter assignments, Henry had worked in the Stewards Branch as a mess attendant. Prior to World War II, minorities were segregated into food service positions, such as cooks, stewards and mess attendants. According to military regulations, these enlisted positions had no petty officer status. For example, an African-American Chief Steward might receive the pay of a Chief, but he held no rank over any other enlisted man on the cutter. Northland’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. Carlton Skinner later recounted how this situation changed with Oliver Henry.

He came to me and asked if he could be examined for the rating of Motor Machinist’s Mate 3rd Class. I had him examined and submitted his papers, which were of the highest caliber. The response came back from the Enlisted Personnel Office at Headquarters that he could not be rated as a Motor Mechanic because he was a Negro and Negroes were only accepted in the Steward’s Branch. I appealed the decision, through channels, and as a result, Enlisted Personnel reversed itself and authorized his transfer to Motor Machinist’s Mate.

When Henry shipped out on board the Northland, he was a Mess Attendant 2nd Class. Within a year, he transitioned to Northland’s engineering section and rocketed through the petty officer ranks. Only a year after joining the engineering staff as a Fireman 1st Class, he made Motor Machinist Mate 1st Class. Just a few months later, at the end of 1943, Henry made Chief. By the time he stepped off the Northland in early 1946, Henry was not only a Chief Motor Machinist Mate; he was Northland’s Assistant Engineering Officer and its Assistant Damage Control Officer. It was a remarkable rise for an African American in a segregated service and proved the worth of every Coast Guardsman no matter their skin color.

Stories that Matter: La'Shanda Holmes

La’Shanda Holmes is no stranger to prevailing against adversity. After growing up in the foster care system, she put herself through college, became a pilot, and amassed over 1,600 flight hours conducting search and rescue, counter-drug, law enforcement, and Presidential intercept missions. In 2015, she was appointed by President Barack Obama to be a White House Fellow.

Only a few short years ago, La’Shanda was a student at Spelman College with a passion for community service. While passing out pamphlets at a school career fair, she stopped to thank Coast Guard Senior Chief Dexter Lindsey for his attendance and service to our country. The two started talking about serving the community and the Coast Guard mission.

Senior Chief Lindsey was impressed by La’Shanda’s ambition and initiative. La’Shanda, in turn, was very interested in the fact that Coast Guard would pay for her tuition, books, and fees for her remaining two years of college.

After enlisting through one of the Coast Guard’s many scholarship programs, La’Shanda finished basic training and later graduated with her bachelor’s degree. She then travelled to places like Alaska and Japan, meeting inspiring people everywhere she went.

During this time, La’Shanda took her first helicopter ride in Clearwater, Florida. In the cabin of that MH-60 Jayhawk, La’Shanda realized what she wanted to do next.

La’Shanda knew going into flight school that there had never been an African American female helicopter pilot in Coast Guard history. But uncharted territory never intimidated her before so she completed flight school and made the record books. La’Shanda has since led countless rescue missions and served her community through her passion for aviation.

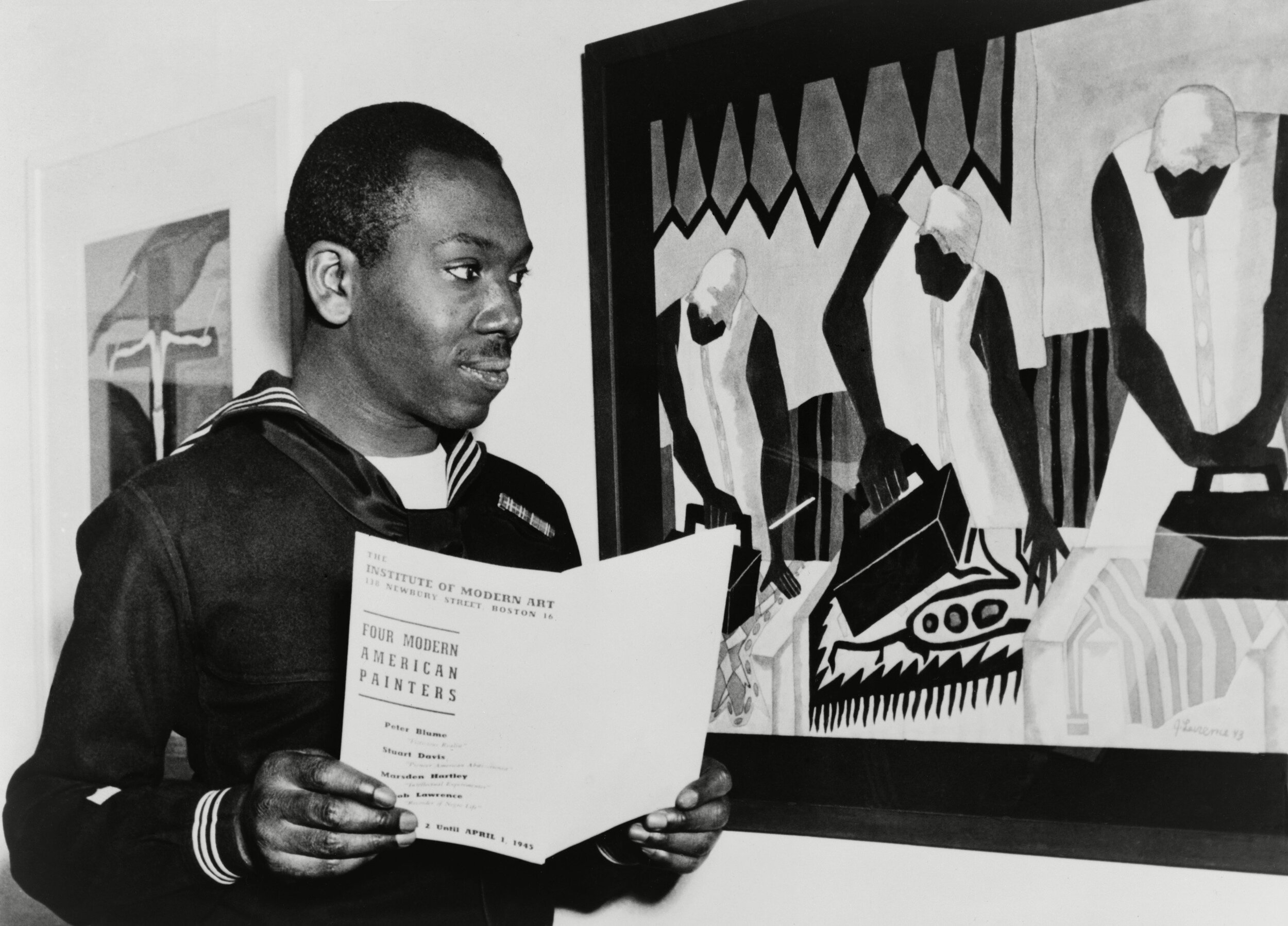

Stories that Matter - Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence’s lifework was the painting of the narrative of African-American history: The accomplishments of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman; the northern exodus known as the Great Migration; the vibrant community of early twentieth-century Harlem.

The Library, 1960

In 1941, Lawrence’s work was displayed in the showing of his 26-panel “The Migration of the Negro” in New York’s Downtown Gallery. The landmark show was the first time a black artist crossed the mainstream art scene’s color barrier.

In 1944 Lawrence’s own life imitated his art when he made history as part of the first racially integrated afloat unit in the U.S. military. That year he joined the USS SEA CLOUD, a yacht converted into a weather patrol ship for the Coast Guard, which was then operating under the control of the Navy. Afterward, Lawrence remembered this landmark experiment in racial equality as “the best democracy I have ever known.”

“I think everyone was really relieved that integration had finally come,” Lawrence said of his time on SEA CLOUD. “Segregation was such a burden to everyone, really. We were like a family on that ship.”

Stories that Matter - Ida Lewis

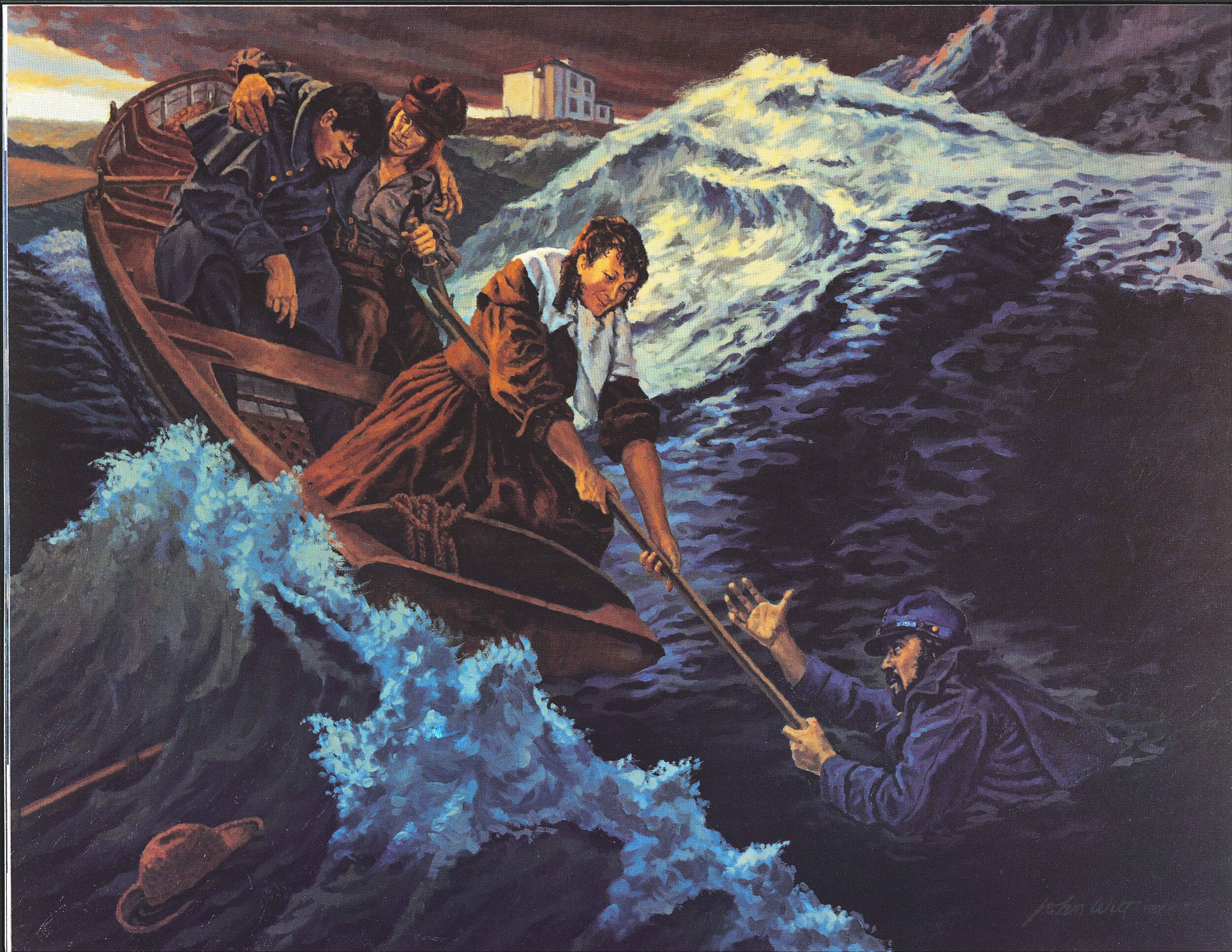

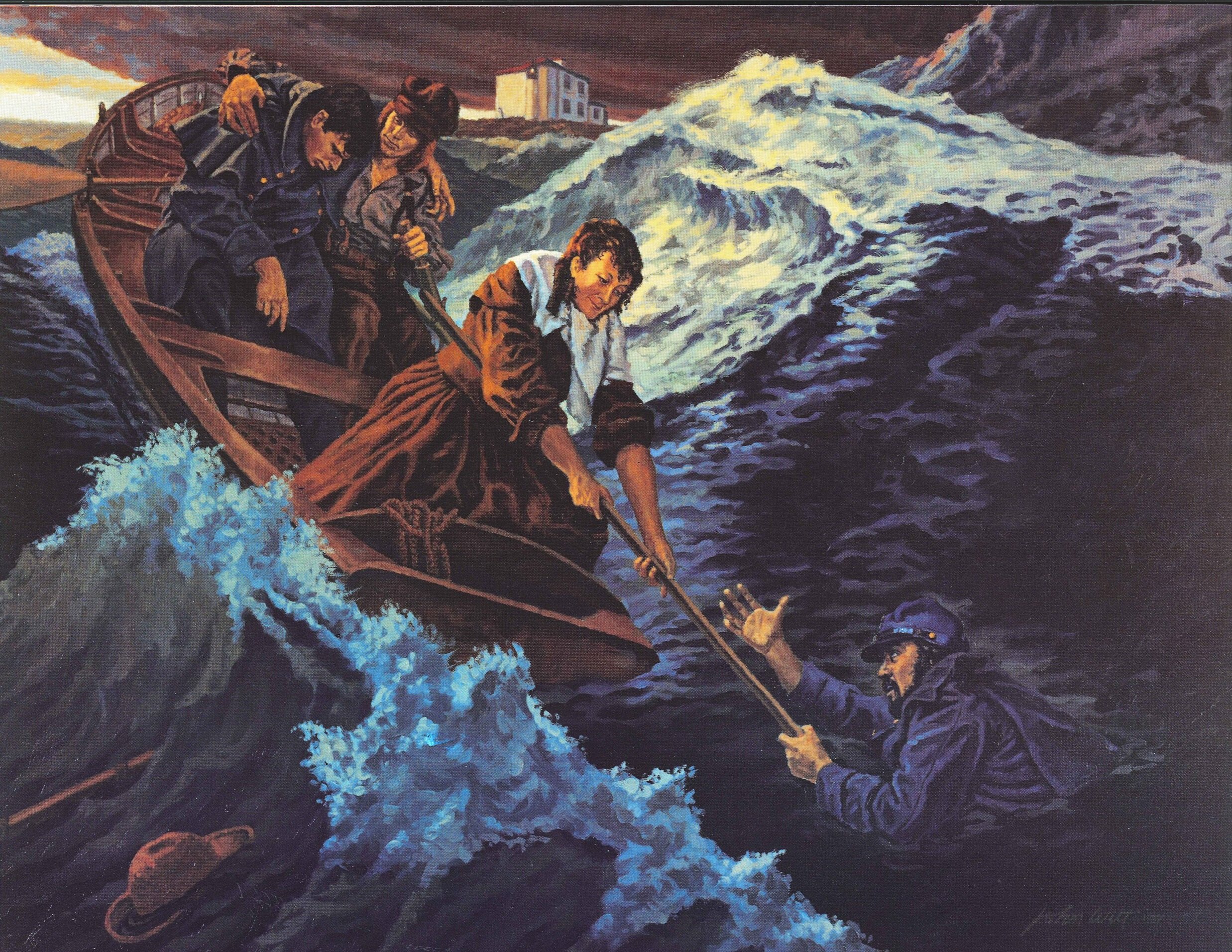

The United States Coast Guard and its predecessor agencies have been blessed with the service of many determined and courageous women. One such woman was Lighthouse Keeper Ida Lewis, recipient of the service’s Gold Lifesaving Medal.

Idawalley Zoradia Lewis, known as Ida Lewis, is one of the best-known keepers, male or female, in the history of the U.S. Lighthouse service. She gained national fame at a time when most women worked behind the scenes with little notice or compensation. Overcoming the biases of the time through skill and professional ability, Lewis served unofficially as keeper of Newport, Rhode Island’s Lime Rock Lighthouse beginning in 1857, when her father, the official keeper, was disabled by a stroke. From 1857 until 1872, she kept the light and cared for her disabled father and a seriously ill sister. Lewis was finally appointed Lime Rock Light’s official keeper in 1879 and served there until she died in 1911.

An expert boathandler, Lewis made her first rescue when only 12 years old. It was noted by others that she could “row a boat faster than any man in Newport.” In 1881, she received the Gold Lifesaving Medal for the rescue of two soldiers from nearby Fort Adams. The men attempted to walk across thin ice from Lime Rock to the fort and broke through the ice into the frigid water. With only minutes before the onset of hypothermia, loss of feeling in their limbs and imminent drowning, the men screamed for their lives. Lewis heard their cries and ran from the lighthouse with a rope. She threw them the line while standing on the ice. In spite of the danger of falling through or being dragged into the water by the two men, Lewis managed to save both men–one by herself and the second with the help of her younger brother.

Stories that Matter - Douglas Munro

Ask any Coast Guard man or woman and any Marine about Douglas Munro and you will instantly be taken back to the fateful day in 1942 when a Coast Guardsman gave his life so a detachment of Marines might live. To a woman or man, each will recite Munro’s last words to his best friend, Ray Evans, “Did they get off?” In many ways, Munro’s sacrifice is at the very core of the close relationship between the two services. And, all who hear Munro’s story instantly understand the bond between American brothers and sisters in arms and the true meaning of service to nation.

Official Coast Guard painting of Munro’s last moments while evacuating Marines at Guadalcanal.

“Douglas A. Munro Covers the Withdrawal of the 7th Marines at Guadalcanal” and was painted by artist Bernard D’Andrea for the Coast Guard Bicentennial Celebration.

“The heroism of Signalman First Class Douglas Munro has inspired generations of Americans who have joined the ranks of the United States Coast Guard. He put service above self, sacrificing his own life to save a Marine detachment under heavy enemy fire at Guadalcanal on this date in 1942,” said Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson. “Author James Michener wrote of such courage in his war novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri, asking: “Where do we find such men?” We find such men – and women – all over America. And they share with Signalman Munro a firm belief in the greatness of this country and a love for it greater than for life itself. For such Americans, we are eternally grateful.”

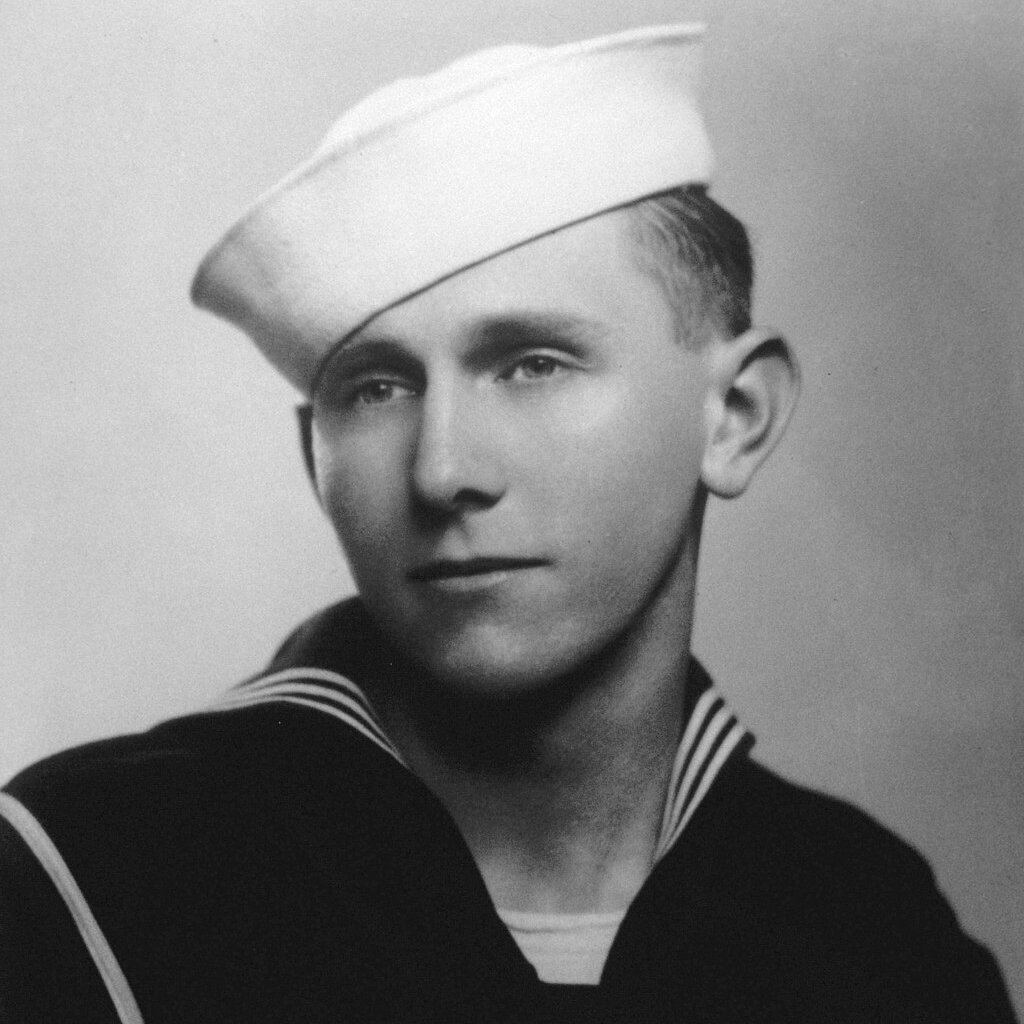

Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro, shown above in a snapshot taken by a shipmate, gave his life while engaged in evacuating a Marine battalion. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Munro is the only person in Coast Guard history to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor.

His story of bravery and self-sacrifice will be told in the Defenders of our Nation Wing, where exhibits will detail the Coast Guard’s role in every major conflict since its inception in 1790.

Stories that Matter - Ronaqua Russell

Lt. Ronaqua Russell made history as the first female African-American member of the Coast Guard to receive the Air Medal for her efforts during the Hurricane Harvey response. She flew through severe weather hours after Hurricane Harvey made landfall to deliver personnel and equipment vital to Coast Guard rescue efforts in Houston.

Stories that Matter - Cutter TAMPA

USCGC TAMPA originally known as MIAMI was built by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Corporation, Newport News, Virginia. Construction was authorized on 21 April, 1910. She launched on 10 February 1912, and was commissioned on 19 August.

Following the sinking of RMS Titanic in April 1912, MIAMI was assigned ice patrol duty with SENECA in 1913, and saw extensive duty as part of the international ice patrol.

That same year, the cutter and her crew participated in the city of Tampa’s Gasparilla Pirate Festival, a celebration of a mythical Spanish pirate. That tradition continued until the United States entered World War I in 1917. The cutter and crew enjoyed a close relationship with the city of Tampa, and was renamed in honor of the city in 1916.

USS Tampa, in Gibraltar

TAMPA, under the command of Captain Charles Satterlee, was one of six Coast Guard cutters assigned to convoy duty in European waters during World War I. Armed with four 3-inch guns, she escorted eighteen convoys, losing only two ships and earning a special commendation for exemplary service.

On 26 September 1918, having just detached from her 19th convoy, and sailing alone through the Bristol Channel toward the Welsh port of Milford Haven to recoal, TAMPA was torpedoed by the German submarine UB-91. Exploding amidships, she sank in just under three minutes. One hundred and thirty men lost their lives, including 111 Coast Guardsmen. Tampa’s 10 African-American crew members were the first uniformed minority Coast Guardsmen to die in combat. They were also the first minority Coast Guardsmen to receive the Purple Heart Medal.

A World War I photo of TAMPA crew members, including African-American Coast Guardsmen standing middle right. Coast Guard photo.

The sinking of the cutter was the single largest loss of life for the Coast Guard during World War I. The sacrifices of her crew were not forgotten. The city of Tampa conducted a fundraising campaign, “Remember the Tampa!,” to an effort to sell war bonds. In 1921, the Coast Guard christened a new cutter in her name. Seven years later, on 23 May 1928, The US Coast Guard Memorial was dedicated at Arlington National Cemetery, honoring the sacrifice of those who had served aboard TAMPA.

Stories that Matter: USS Sea Cloud first integrated U.S. Warship

In 1943, the Coast Guard-manned USS Sea Cloud became the federal government’s first deliberate test of desegregation in a U.S. ship.

Lieutenant Commander Carlton Skinner Skinner first reported aboard Sea Cloud as Executive Officer in November 1943. He took command after his first weather patrol and oversaw the first experiment in racial integration on board a U.S. warship. Earlier, he sent a memorandum up the Coast Guard chain-of-command recommending training for African-American seamen in ratings other than food service, the only ratings open to people of color at that time.

The integrated crew of the USS Sea Cloud

The Commandant approved Skinner’s request and began assigning black seamen to the Sea Cloud. Within a few months, there were over 50 African-Americans assigned to the Sea Cloud. The cutter’s crew included Lieutenants Joseph Jenkins, Clarence Samuels and Harvey Russell, Sea Cloud’s black commissioned officers.

Jenkins and Russell had graduated from the Service’s Reserve Officer Training Program at the Coast Guard Academy while Samuels came up through the enlisted ranks. Skinner had requested no special treatment or publicity and the Sea Cloud successfully carried out its missions like any other warship assigned to weather patrol duty.

Skinner reported no significant problems and the Sea Cloud passed two Navy Atlantic Fleet inspections with no deficiencies.

Stories that Matter - YOCONA Pioneer in vessel design and desegregating cutters

Throughout the history of the U.S. Coast Guard, the nation has tasked the service with new missions to respond to all sorts of maritime threats and crisis. Such was the case with the Great Flood of 1913, considered by many as the most devastating flood in U.S. history.

Photograph of a man and wife in Dayton, Ohio, stranded on top of their front porch during the Great Flood of 1913. Photo courtesy of Wright State University.

Because of this natural disaster, Congress voted to fund federal flood relief and rescue work on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. On Aug. 29, 1916, it passed a naval appropriations bill that included money for the construction of three “light-draft river steamboats” for the Coast Guard. Their mission was to “give relief, succor, and assistance to victims of floods” on the two major river systems.

Picture of a flotilla of Coast Guard 23-foot patrol boats rafted next to a Coast Guard river cutter. Photo courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

Of the three “river cutters” funded by Congress, only two were completed. These were the cutters YOCONA and KANKAKEE. The service commissioned them both on Oct. 19, 1919, and stationed the Kankakee on the Ohio River at Evansville, IN; and the Yocona on the Mississippi River at Vicksburg, MI. Yocona took up its station on Jan. 18, 1920. As the earliest river cutter to carry out its duties, Yocona became the first Coast Guard cutter of any kind to operate on the nation’s inland rivers.

In addition to Yocona’s specialized design, the cutter proved unique in the nation’s history of racial desegregation. Within a year of Yocona’s commissioning, it received an entirely black enlisted force while Kankakee’s crew was composed of only white officers and men. With the exception of officers and non-commissioned officers, Yocona’s enlisted crew was entirely African-American, including petty officers in every rating.

A rare image of Yocona’s crew in 1925 shows the black enlisted men, and white officers and non-commissioned officers posed on board the cutter. Photo courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

By recruiting an all-black enlisted force of petty officers, Yocona’s officers had set a precedent for desegregating the nation’s sea service vessels. While Yocona may be the first desegregated federal ship in American history, the Service never publicly recognized the groundbreaking cutter as such. More than likely, the Coast Guard recruited the best-qualified watermen near Yocona’s homeport of Vicksburg. The fact that the Coast Guard operated a cutter with an integrated crew 100 years ago is history making in itself. However, the fact that Yocona was homeported in a state that held the nation’s worst record of discrimination and violence toward blacks makes this achievement all the more remarkable. Atlantic Area Historian, Dr. William H. Thiesen provides further detail on this barrier-breaking cutter.

Back to Top

Back to Exhibits